The American poet

October 18, 2024

Si Ting Chen

Si Ting ChenIn his 1844 essay “The Poet,” Ralph Waldo Emerson asked into a void: ‘Where is the great American poet?’ Where is “the man without impediment, who sees and handles that which others dream of, traverses the whole scale of experience?” To him, the poets must be our “liberating gods,” meaning that they incite our latent capacity to see beauty and enliven our imaginations. Liberty here is both a freedom to perceive what we ignore—beauty, joy, youth—and extrication from the narrowness of what we believe must be—the obligations and mechanisms of modern life. When we have forgotten how to perceive beauty, the poets draw us to the pool of memory and urge us to drink. Emerson was convinced that a poet with such power was destined to spawn from American soil and clear the fog from our eyes.

You cannot read “The Poet” without refashioning American history typologically. Walt Whitman must come into being, so naturally, Emerson announced his imminent arrival a decade prior, as John the Baptist arrived to herald Jesus (a connection made by Harold Bloom in his introduction to “Leaves of Grass”). Whitman’s preface to “Leaves of Grass” reads as a letter in response to Emerson, a cry of “I am here!” He defines Emerson’s poetry in his own terms, most convincingly when he writes, “The greatest poet hardly knows pettiness or triviality. If he breathes into any thing that was before thought small it dilates with the grandeur and life of the universe. He is a seer … he is individual … he is complete in himself … the others are as good as he, only he sees it and they do not.”

The central aim of “Leaves of Grass” lies in that last line. Not everyone is a great poet or has the vision of one, therefore it is the great poet’s task to mint his perceptions into something tangible and see for those who cannot. You could say that not everyone will be capable of understanding the poet’s output, but I counter you with Whitman’s openness, exuberance and simplicity. He addresses us directly and unabashedly, the way an intimate friend would. You already know him. He has walked alongside you and watched the grass unfurl from your soul.

At the start of the 19th section of “Song of Myself,” he writes:

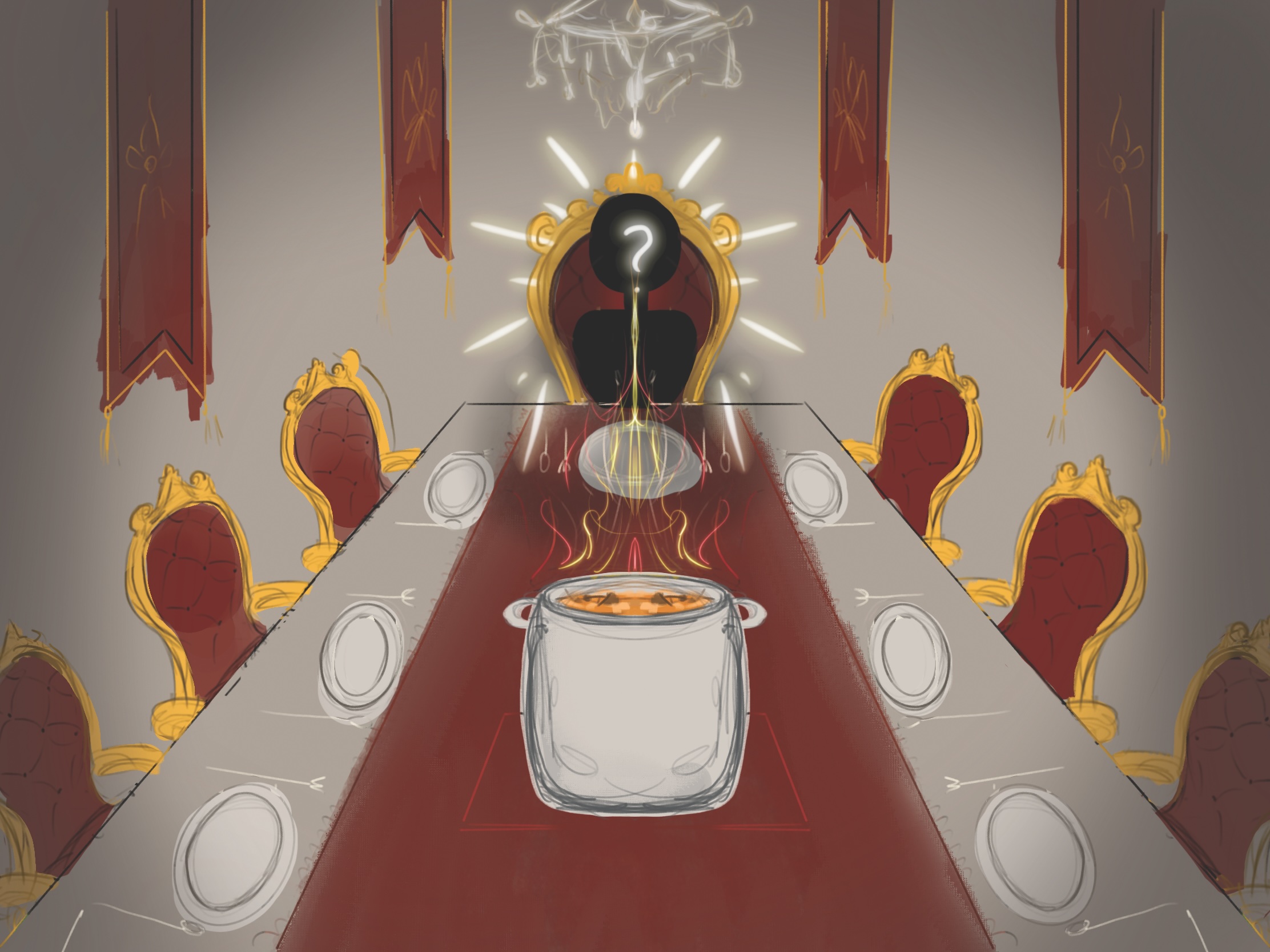

“This is the meal pleasantly set …

this is the meat and drink for natural hunger,

It is for the wicked just the same as the righteous …

I make appointments with all.”

This “meal” is one of his wisdom and clarity, and he has set the table for each and every one of us. To have a soul is to be present at this meal, regardless of what wickedness or goodness you choose to channel yourself into. To Whitman, the soul exists beyond our moral distinctions. In other words, to nail a soul down on its being “righteous” or “wicked” is to miss the point. Our souls propel us down avenues of the unexplainable, and we understand others’ propulsions as solar flares of their own souls.

Any half-present observer can concur that our modern unhappiness stems from how we judge one another. Whitman writes beyond the common markers of value that divide us and pit us against each other. Wealth, class, eminence of profession—these all mean little to him in the face of the inimitable soul. There is significant beauty to life and life alone, that he venerates. The life of the soul is beautiful and important in every corner of our nation.

However, he counters the notion of an American “melting pot”—the idea that we must all submit ourselves to some unifying change, or that the American setting does that of its own volition. Some innate Americanness is embedded in our souls and makes us equal. We all belong to a great tapestry, glittering threads sewn together by the only one up to the task: the American poet. Some of Whitman’s most valuable work is done in the rambling lists of “Song of Myself,” where he roves the plains for a glimpse of the duck-shooter and searches the city streets for clean-haired factory girls. Altogether, these images compose the American poem—a poem of energy and apathy, triumph and travesty. Beauty appears in the distinctly unbeautiful—drunks at barroom stools, lunatics carried to asylums, sick infants. There is poetry in it all.

Whitman responded to Emerson’s call, and I make a similar call now, though retroactively. Many poets have done the same—Wallace Stevens, Hart Crane, Stephen Vincent Benét—conjuring Whitman’s ghost out of Paumanok shores and clouds of Midwestern dust, begging for a kernel of his knowledge. How foolish to ask him for a postscript when his essential text is already there for the taking! It is America’s greatest cultural output, an assertion that Emerson made then and I second now. Indulge in his wisdom—it is your inheritance as much as it is mine.

More than any poetry I will write about this semester, I believe in “Leaves of Grass.” It is a salve for the soul. When I finished it this summer—admittedly at four in the morning—I stepped outside into the night rain, watching the street in front of me. The mundanities that I take for granted—the dark asphalt, the old street lamps, the light-polluted sky—all were reinvigorated with a new life. No, it was no “new” life that my reading had breathed into it—I was aware of an ancient, thrumming life that I hadn’t cared to search for before. It was—and is—a gift.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: