Q&A: Marroquin discusses changes in enrollment following affirmative action ban

September 6, 2024

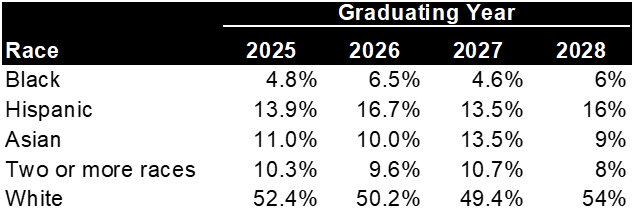

Data released by the College on Wednesday revealed the racial and financial makeup of the Class of 2028, the first to be affected by the Supreme Court’s ban on race-based affirmative action last year.

The class saw a slight decline in the percentage of domestic students of color, from 42 percent to 39 percent. The percentage of first-generation students decreased from 21 percent to 16 percent.

Shihab Moral

Shihab MoralClaudia Marroquin, the dean of admissions and student aid, said in an interview with the Orient that it is difficult with just one year of data to tell whether the dips are a result of the Supreme Court decision.

The economic composition of the newest class did not significantly change. The share of students on financial aid went up from 51 percent to 53 percent, while the average financial aid award declined marginally, from $69,000 to $68,000.

In the transcript below, which has been edited for clarity and brevity, Marroquin spoke about these statistics, her interpretation of them, and the new methods the admissions office has begun to employ to recruit a diverse student body.

Can you start by telling me what you and your colleagues’ reactions were to this first batch of post-decision data on the Class of 2028?

I mean, we were all waiting to see what the data would look like—our own and what other colleges would be reporting—and it’s hard to describe any feeling because what we’re seeing from other colleges are varying results. Some colleges have had significant decreases [in racial diversity]. Others are reporting increases. Others have seen some changes, but whether we can attribute them to the Supreme Court decision or not, that one year of data won’t be able to tell us.

I will be candid: There was a little bit of a sense, not of relief, but the worst did not happen, at least at Bowdoin.… I think it’s mixed emotions, because we are learning every day about different reports at different institutions and just trying to make sense of it all.… We’ve spent time with our data … and it appears as if our efforts to recruit students held. But certainly, there’s more work to do.

You mentioned last year that to build a broadly diverse class, admissions is visiting more Title I schools and looking more closely at whether applicants are Pell-Grant eligible and if they would be first-generation students. Do you have a sense yet of whether any of those strategies have been particularly effective? And will you be putting more or less effort into any one of those strategies this year than you did last year?

I think all of those strategies are going to continue to be efforts that we look at as we head out on travel. We’re continuing to think critically: Where are there students with whom we may need to be in person and to hold events that are open, not just at high schools but to the larger public? And for which high schools is it necessary for us to be on that actual campus, because students may not have the opportunity to travel to an evening event and whatnot? And that varies school by school, region by region. We don’t visit all of the exact same schools every year—there’s only 15 of us.

…

Last year, one of the efforts we did in the yield process was partner with the three established alumni affinity groups. They were wonderful to work with us to host webinars after admissions decisions had been released. We sent invitations to students—anyone who was admitted received an invitation—to hear from alums about their experiences, what their trajectories have been. And I think that also helped and contributed to students feeling informed and knowing that these issues are critical at the College, and that the College is thinking about the entire pipeline.

Does the admissions office have any exact measurements that tell you whether visiting Title I schools leads to more applicants from those schools?

I have not seen, necessarily, the data on outcomes from one year, because sometimes, especially at Title I schools, we might be asked to present to juniors. So some of the travel we do is about setting the roadmap for the future, rather than an immediate result, for that applicant pool. So I have not been able to dig into how many applicants yielded from any one specific school visit.

You mentioned there is a lot of variation in the data between colleges across the country. What kinds of differences are you noticing between the data at Bowdoin and that of other schools?

I’m seeing the same articles that I’m very sure you have read and that others are looking at, so the only real data points I have are the ones that are publicly available. And I don’t know the changes that individual offices have made; there are a lot of things that colleges can’t share amongst one another about our individual processes…. There is data that will help inform assumptions and theories we might have when Common Data Set [an annual report about the college admissions and financial aid process] information becomes available, and we get to see a little bit more nuance.

But I think every colleague that I know at colleges like Bowdoin has been committed to the work in the same way we have. And there’s the things we can influence, and then there’s also the fact that this is a process where students have a final say. I recognize so much of the conversation around the Supreme Court decision is focused on admissions offices and the decisions we make, but so much of what happens and how students enroll at schools comes down to the choices that students are making, which vary from year to year. And I don’t know if there are changes in the behavior of students following the Supreme Court decision.

The other piece that we will not know for years is the impact of changes to the FAFSA [Free Application For Federal Student Aid] rollout and what it has done to yield. The federal government made changes to the application.… It usually opens on October 1, and given the simplification process they were undergoing, there were several delays. The form did not become live and available until December 1, I believe, but then there were issues where most colleges did not receive any data from the federal government until March…. So institutions that don’t have another mechanism for awarding financial aid were unable to do so for millions of students across the U.S. And while we use the [College Scholarship Service] Profile, we did have conversations with students who were waiting to hear from state schools about awards. And what impact that had on students of color or first-generation students for yield overall is still another area where we really need more time and research to understand. So a lot has happened this past year, and it’s hard to say that anything is going to be related only to the Supreme Court.

Let’s talk about the numbers Bowdoin’s seeing this year. As you mentioned, the changes are relatively minor. Do you have any sense of what changes—such as the slight decline in the percentage of students of color—you can attribute to the Supreme Court decision?

I would be making conjectures, because they’re not significant differences, and I say that acknowledging that students may feel that they are significant. But we will see fluctuations from year to year…. It’s hard to say that any of these changes can be attributed to any one thing, because they’re not so dissimilar from previous changes that we have also seen.... It could just be a natural blip, or it could be something larger. So we need more data to be able to say if it’s a trend or if it’s something that just happened as a one-year occurrence.

Would you also say that about the decline in the number of first-generation students from 21 percent last year to 16 percent this year?

That is one that I’m disappointed with. And that one is hard to tell. It could be issues with the FAFSA. It could also be that students have more choices…. It’s hard to tell off of one year’s data, but that is a statistic that was hard to look at and to see throughout the cycle that we were likely going to be at a lower rate of first-generation college students.

You’ve said the admissions office can’t see a student’s race(s) on their application, but Bowdoin does have an optional essay about “navigating through difference.” Bowdoin also offers an optional video response, which in some cases could make the applicant’s race visible. When you have information about someone’s race, in what ways are you able to consider it?

So if you go back to the language from the Supreme Court decision, Justice Roberts is clear that race can be considered when it talks about a student’s lived experiences and the inspirations they draw from those experiences. And that’s one of the pieces where in holistic admissions, I do feel strongly that we have always looked at the experiences students have had and how their identities, whether it’s race or any identity, have influenced those experiences and the values, the strengths and the beliefs they would bring to our campus.

So the “navigating differences” essay is not prompting students to talk about race, but it’s around how they’re navigating differences of lived experiences, of opinions, and we saw the huge spread of what students were sharing and choosing to talk about. So in those essays or in the personal statement, if a student is talking about their lived experience … that can be considered because you cannot separate a person’s experience and the values they draw and inspiration they gain from those moments.

And our video response is a similar piece where we are looking at what the response is, the content of the response to the question that the student has received and aligning that with how then the student might be able to contribute to our campus. So we are leaning directly on the words that a student is utilizing.

I want to ask you about a debate that’s taken place over the years and is being reignited in wake of the data released from other schools. At MIT, there’s been a slight increase in the percentage of low-income Asian students and a decline in the number of high-income Black students. And there’s a debate over whether that’s good or bad. Do you have views on whether socioeconomic status is a better method of increasing campus diversity than race?

I think this has come up in different iterations at Bowdoin, where we value diversity in all of its forms. There’s the strength of having socioeconomic diversity, because the United States is a socioeconomically diverse country. And we need students to be grappling with what access to opportunity means based on income. And when it comes to race, the experiences of a person in our society, whether they are low-income or not, are going to vary. They are valuable as well. So I don’t think any one is better than the other. They’re all necessary to have an informed student body and to be able to grapple with really big issues on our campus that cut across all these different forms of identity.

Before the Supreme Court decision last year, affirmative action was legal, but only as a way to benefit the student body and the College, not for the sake of making up for historic inequities. I’m sure Bowdoin abided by that law, but do you have views on whether affirmative action should be a tool for undoing injustice?

That is a very complicated question, and one I would prefer not to weigh into because it’s hard to distinguish personal opinion from an institutional role.

Editor's Note on September 6 at 4:45 p.m.: The original version of the article stated that Bowdoin saw a slight decline in students of color, from 42 to 39 percent. This statistic actually represents domestic students of color.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: