Making meaning while mourning in place

April 24, 2020

It’s mid-afternoon on a Monday, and my ability to focus is at an all-time low. I’m in my bedroom at home, sitting at my desk. On my laptop screen, an instructor from my abroad program is starting a remote class session from her home in southwest England. I try to silence my thoughts and listen to her, but my hands are shaking and sweating. Less than a minute into the class, a framed photo on my desk catches my attention, shattering my fragile focus and sending flutters through my chest and tears to the corners of my eyes.

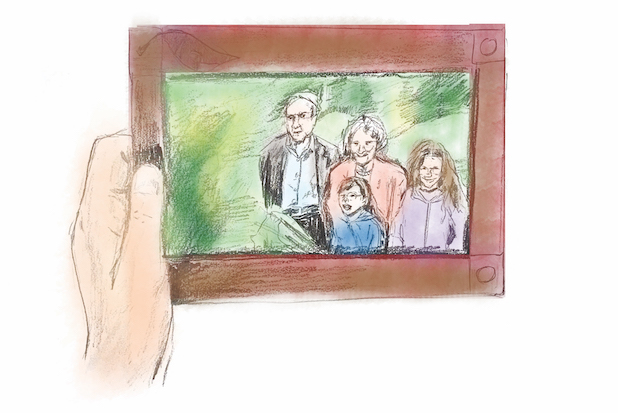

It’s actually only one corner of the picture that remains unobscured by my computer: my grandfather’s face. Surrendering to the distraction and hoping my instructor won’t notice, I push the laptop aside and allow myself to stare at the photo.

Taken nearly 15 years ago, it captures me, aged six; my sister, aged nine; our grandmother and our grandfather. We’re posing together at the end of a dance recital. My grandmother stands behind me, in between my sister and my grandfather, with an arm wrapped around the front of my torso. My grandfather stands with his hands clasped behind his back, dressed in a button-down shirt and sport coat, looking as though he’d been in the middle of speaking when the photo was taken.

Back in the present, I sit frozen, trying to figure out what to do about my class as I feel the tears threatening to spill over. It’s been about 15 minutes since my mother told me that my now 96-year-old grandfather, who was admitted to the hospital in New Rochelle, New York on Friday, has tested positive for the coronavirus. I shift my gaze to the right, where a card bearing a picture of my grandmother’s face balances against my desk lamp. We’d had the card made only three-and-a-half months earlier, after her sudden death on the last day of classes in December, which hastened my departure from school and led to me completing my final papers from home—a painful memory that is becoming an increasing source of déjà vu.

I manage to get through Monday’s remote class session, but the next seven days become a blur of hours spent on hold, updates on continually changing vital signs and rushed conversations with the overworked but incredibly diligent team of doctors and nurses staffing the coronavirus floor at New Rochelle’s Montefiore Hospital. He seems stable; now he seems worse; now there’s hope; now there’s not. My dread and confusion increases as his fight with the virus drags on. Restorative sleep is replaced by nightmares and waves of anxiety. We can’t visit him, so we concentrate on sending him mental messages, on imagining we are holding his hand.

And then, suddenly, it’s over: a phone call from the hospital, an assurance that he had died peacefully. I had dreaded the sound of my mother’s ringtone for 11 days, but suddenly I’m seized with a fierce wish for it to keep ringing. I longed for more updates, for more news of any kind other than that which we had just received. But, after my grandfather had fought harder and longer than any of us or his doctors expected he would, the time for updates had passed. I know that he is now at rest, having joined my still newly-departed grandmother.

And yet, inner peace still eludes me. We phone in for the burial that we can’t attend, with my sister and her partner standing six feet away from me and my parents in our backyard, a bouquet of flowers on the ground between us. I think back to December, when I watched my mother and her sisters hold hands as we walked away from my grandmother’s grave, when we were able to come together to partake in ancient rituals that made me feel a bit less helpless in the aftermath of death. In the age of the coronavirus, all of this has to be postponed; there cannot be such a gathering in an age of social distancing. Instead, while sheltering in place, hundreds of thousands of families will have to figure out how to mourn in place as well.

Then comes Holy Week and Passover, the first of either since the death of my Jewish grandmother and, now, my Armenian grandfather. We have a family Zoom seder on the second night of Passover, and I sit with my mother to watch two live-streamed services on Easter morning, one Armenian Orthodox and one Episcopalian. Having this multifaceted heritage has not always been easy, but this year it’s somehow incredibly inspiring; I feel more hopeful after hearing these different groups use major holidays to spark conversations about how this pandemic can be an opportunity to be more generous, compassionate and loving than we were before.

This message makes me think of all of the examples of selflessness that already surround us. I’m reminded of my grandfather’s courageous doctors and nurses, especially the nurse who helped our family arrange the phone call that allowed us to say goodbye. I’m also reminded of all medical professionals; of all essential workers (especially those who are marginalized or underprotected); of all families mourning a loss or fearing for the future; of everyone who is struggling to make it through this truly challenging period but still finds it within themselves to reach out to a loved one, friend or stranger.

None of us know what the other side of this pandemic is going to look like. I know that, for me, this period will always be a deep source of sadness. I also know that I still have hope, and I feel truly lucky for the people in my life who I can look to for love and support. This still includes my grandparents, whose faces I see echoed in my own whenever I look in the mirror. I think of my grandfather’s enduring sense of humor and incredible strength and of my grandmother’s wry smile and deep commitment to her family, and I know they are still with us.

But even as I process my own loss, I also feel called to action. I’m privileged that I’m able to grieve without worrying about going hungry or not having a place to live, and I feel devastated that this is not the case for so many. I think about my grandparents’ families—pogrom and genocide survivors who sought refuge in the United States—and I feel deeply saddened that inner-city immigrant communities in our country have been left especially defenseless against this pandemic. I know that my grandparents, progressive-minded people who were deeply involved in fighting for equity in their communities, would’ve felt the same. I hope that, after this pandemic has passed, we remember what it has taught us about what we must prioritize if we aspire to continue building a more just, equitable and compassionate world.

Nina McKay is a member of the Class of 2021.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Dear Nina, Thank you for sharing this heartbreaking story. My deepest condolences to you and your family on the loss of both of your grandparents. My thoughts and prayers are with you and your family. Please know, at least one person read your touching essay and was moved by it. Hope you are able to return to campus next year and complete you Bowdoin experience. Your are an excellent writer. Sincerely, Joe Leghorn ’74