Damn the discourse: a liberal dose of mush

September 22, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

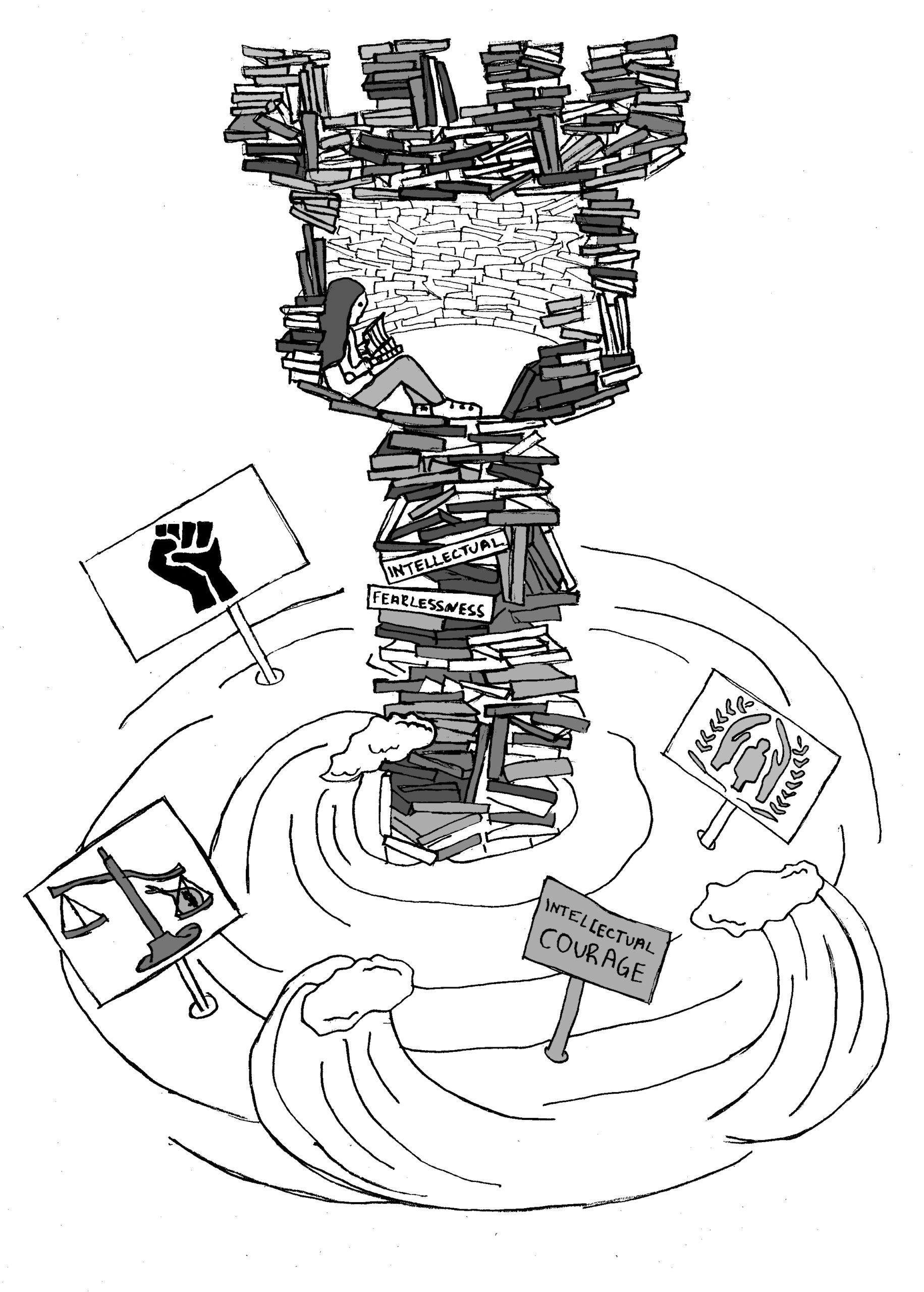

President Clayton Rose published an op-ed in TIME Magazine arguing for the importance of the liberal arts. Roughly, his argument is that today “intellectual engagement is too often mocked,” leaving us in a “distressing place… where facts are willfully ignored or conveniently dismissed” and where “Hypocrisy runs rampant and character appears to no longer be a requirement for leadership.” His proposed solution is one we’ve heard from him before: intellectual fearlessness, the notion that one “can consider ideas and material that challenge their points of view, which may run counter to deeply held beliefs, unsettles them or may make them uncomfortable.”

I take issue with much of Rose’s argument, and what I find most troubling is his seeming inability to articulate, with substance, a goal, mission and role for the liberal arts that extends beyond banalities. There is a crisis in higher education—and in our politics more generally—and, indicative of this crisis, is the pablum that Rose again serves us. Action is in order, and to begin we must find something stronger than mere platitudes couched in instrumentalism. President Rose and I agree, we have found ourselves in a “distressing place,” but I am unable, at “this challenging moment in our society and world,” to muster Rose’s optimism.

An underlying focus of Rose’s piece is ‘the discourse,’ a sacred cow of centrists and of a cadre of elites. The discourse privies process over policy; what matters to its champions is not what is being said but, instead, how it’s being said, feel free to gut what’s left of our country’s social safety net, they imply, just make sure you use your indoor voice. When you prioritize discourse, no idea is too bad or too cruel as long as it can be concealed in some convenient opaque phrase: “means-testing,” “block grants,” “self-deportation.”

The emptiness of this position is evidenced in Rose’s almost reflexive equivocation of the two parties—“this is decidedly a nonpartisan problem”—that follows his description of our current politics. This claim is demonstrably false. But what makes this political obfuscation on the part of Rose—and of those of his intellectual ilk more broadly—so worrying, is not that it is wrong, but that it suggests the speaker is simply, terrifyingly removed from our politics. The Republican party in the Reagan era (an era in which we still live) rides in a hermetically sealed coalition that is unmoved by facts or any modern conception of science, turning it into a veritable breeding ground of conspiracy theories. Certainly, fanatical voices on the Left do exist, but we’d be mistaken to see them as equals to those on the Right: there are, first, important ideological differences between the two, but also, just consider that the latter runs our country while the former is relegated to the fringe.

I propose (and this conversation has already begun) that we look for a new standard for substantive intellectual engagement: how about intellectual courage? Rose’s formulation of intellectual fearlessness seems to have been the offspring of several focus group and engineered to be so vague and agreeable that it is drained of any meaning at all. That hardly seems fearless. This may seem like splitting hairs, but there is a crucial difference between courage and fearlessness. Courage means facing the truth in all its ugliness, in spite of our fears. This is far different than merely being “uncomfortable” or, as the word fearlessness implies, ignoring what should, rightly, be terrifying. Because to be fearless now is to be hopelessly naive: quietly, insidiously; Republicans continue to pass restrictive voter ID laws, blocking any chance at democratic recourse; white supremacists are marching unmasked in the streets; and Republicans continue to deny the scientific consensus on climate change, condemning maybe millions to death.

In critiquing this idea of the ‘discourse,’ I do not mean to suggest the need to advance a certain partisan agenda. Truly, this is not some question of Right or Left, indeed what we need now more than ever is a politics built upon a vigorous and substantive exchange of ideas, rooted in the lived realities of people. We must reject a conversation of aerial abstractions that devolves into a wild goose chase in search of some nebulous “common language.” Because encoded in appeals for a “common language,” which seems so neutral, lies an ideologically-charged position: one that prioritizes tone above all else, which been disastrous for our nation. It has allowed Far-Right extremists to undermine the academy, poisoning the debate Rose claims to value.

Most distressing of all though, it has lead many to lose faith in democratic politics altogether, believing it can no longer yield solutions that will actually better their lives.

Calls for “intellectual fearlessness” which consist of nothing more than dressed up “both sides”—isms has laid bare the danger of these politics of politeness. It has hollowed out our politics and so it should come as no surprise that, faced with this vacuity, many young people are flocking to the Far-Right. People are driven, and politics are fueled, by a shared vision for the future, no matter how noxious. All over the Western world, social democratic parties have faded. I’d argue this is owed in part, to the fact they have become parties of process or technocratic liberalism. They’ve forgotten that the goal of politics is not simply to pass legislation or to balance the budget, but to build a more decent, more just world.

The task at hand now—a task in which the liberal arts will no doubt play a crucial role—is in creating a politics which transcends the boundaries constructed to protect centrists’ tonal sensibilities. Doing so will require diversity of thought that is truly far-ranging because, make no mistake, behind so many of the bland calls we hear from the administration for “dialogue” and “inclusion” lies not the inclusion of marginalized people or the Far-Left, but a tacit an insidious political commitment to the right donors.

The moral hollowness of the idea of “the discourse” has seeped into our understanding of the liberal arts as an institution and idea. Take, for instance, Rose’s use of the word “skill” in his op-ed—he makes the point, three times, that a liberal arts education will give you skills. Contrast this, to last year’s speaker at Baccalaureate, Hannah Holbert Gray, president emeritus of the University of Chicago, who advised the graduating class to “care more deeply for wisdom than for expertise.” Skill, like technical proficiency, allows one to succeed within a system; wisdom, however, allows one to question a system. President Rose’s misconception of the liberal arts is betrayed here by his unconscious alteration of his friend’s words. We must ask ourselves now, at what seems to be a critical juncture, if all the liberal arts is a technical education augmented by an English course or two or something more. I, for one, certainly hope it is the latter. I hope the liberal arts can be an education that both promotes human freedom in all its manifold possibilities while allowing us the chance to connect with those around us, to build communities and—in the long run—to build a better world.

As a first step, let us commit to asking questions more substantive than “how do we talk face to face when we don’t see eye to eye.” Intellectual courage means that during Arthur Brooks’ upcoming visit to campus, we should be prepared to challenge him on the AEI’s support of the Saudi air war in Yemen, tax cuts for our nation’s wealthiest or a repeal of the Affordable Care Act that would leave millions uninsured. Let’s not provide Brooks another platform to bemoan, unquestioned, how a bunch of 20-somethings are harshing his Koch-funded Conservative mellow. Rather, why not strive towards radical political awareness—that is, awareness of the actual stakes of our politics. We need to understand the implications and motives of contemporary political language, as well as, and crucially, the consequences of today’s political debates: what’s at stake, what are we losing and what are we doing morally, by giving into the sanctification of the ‘discourse.’

Intellectual courage and a reinvigoration of the liberal arts is more crucial now—especially with the rise of the Far-Right—than ever. Let us join together to create an idea of the liberal arts that doesn’t feed into the soulless hyper-individualism of American capitalism, but instead transcends it. Let us demand and create an idea of the common good (an idea which walks hand-in-hand with the liberal arts) that consists of more than merely corporate scraps. Maybe, just maybe, reading all that Plato while concurrently learning physics will give us the wisdom to draft a blueprint of a better future: a future that is altogether more compassionate than the present we have. Instead of focusing on tone, let’s fight for a better world—because that’s the only way we’ll ever get one. Damn the discourse.

Ethan Winter is a member of the class of 2019.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Genuine question: what is the thesis of this column? Let’s make the world a better place . . . by doing what I say without any disagreement or discussion? By giving no consideration to ideas outside of my own? By building isolated intellectual communities that are unable to understand, let alone influence, a wider world made up of people who have diverse viewpoints that do not exist on the binary spectrum of “left” and “right”? To dismiss [or dam?] public discourse by waving away the unpleasant reality that people disagree with you, and may wish the express their disagreement just as you do?

I’m not trying to strawman you (although you insist on strawmaning, like, pretty much everyone). I am just trying to understand the point of this somewhat difficult piece of writing.

Ethan Winter has produced the most cogent and pertinent editorial I’ve read in this paper. Kudos to him for calling out President Rose and speaking common sense.