Running circles in the sand: on photoshoots and feminism

February 15, 2019

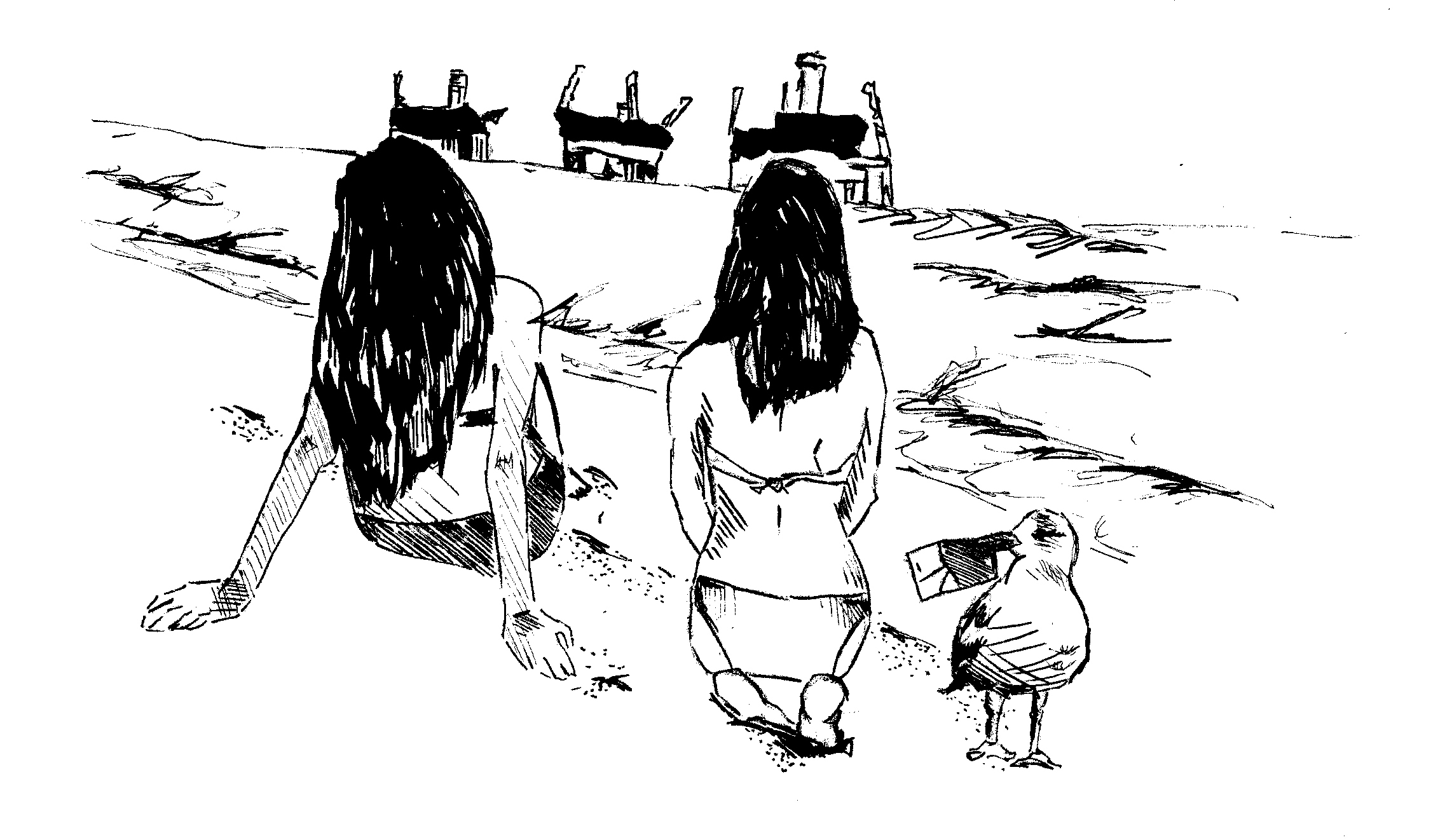

We were squatting on the edge of the waterfront, warm brown waves lapping at our sand-speckled limbs. Oil rigs winked in the distance, the roar of a Confederate flag-adorned pickup truck occasionally punctuating the lazy ocean breeze. We call this: paradise. To others, it was simply spring break in Port Aransas, Texas. 2018.

But though the day had dawned bright and clear, the horizon held a different hue than when we were last here. Empty stretches of sand yawned on either side of us, and the roar of the A/C was all there was to cut through the silence at the seafood restaurants in town. Hurricane Harvey had come and gone, leaving Port Aransas in the throes of rebuilding and rebranding. Adjusting the straps of our swimsuits, we took in the vast expanse and the now-desolate surf.

Our minds turned, as they so often do in exposed and exceptional spaces, to another space of hypervisibility: the “Celebrating Women, Celebrating Bodies” photo exhibits that occur biannually at the Center for Sexuality, Women and Gender (formerly the Women’s Resource Center). We were two Bowdoin 20-somethings, comfortable in our bodies and down with the mission to de-stigmatize the female nude. Showcasing our nude bodies in the middle of David Saul Smith Union would be, as it were, on brand.

But we found ourselves hesitant. Like so many displays of feminism at Bowdoin, this one seemed to validate itself in its capacity to loudly proclaim a somewhat obvious, tired truth: women’s bodies—in all their variations—are beautiful, and hung up on a wall, they make for beautiful images. It speaks to a kind of feminism centered on body image, sexuality and the inescapable pull those exert on our psyches—with little reach into the ways that women’s bodies are regulated and politicized in our current day.

The exhibition billed itself as an opportunity for women to participate in a liberating form of self-representation. But in the age of Instagram, we are all experts in the art of self-representation and performance. Hanging up artfully lit photos of women in the nude places them in a context with which we are all too familiar: on the screen, in the frame, little pixels arranged for our consumption.

We are reminded of Judith Butler’s words on performativity. In an interview with Liz Kotz in Artforum, she writes, “This is not freedom, but a question of how to work the trap that one is inevitably in.”

As women, we spend a lot of time thinking about how we look. The photoshoot revels in this, mattes it on a wall and calls it empowering. It’s a confusing time to be a young woman in the United States, we declared to the gulls rifling through a nearby clump of seaweed. On the one hand, we want to be successful, thoughtful women with careers driven by our brains and our ambition. On the other hand, we exist in a media and pop culture landscape saturated by images of Instagram models and body positivity sirens alike.

When models-verging-on-cyborgs accrue capital with each heart-shaped like, the line between celebrity and layperson, businesswoman and wellness guru, begins to blur. Glued to our own social media accounts, we create this landscape as much as we consume it. The photoshoot takes this dynamic of consumption, one we’re used to seeing play out on our screens, and leverages the fact that its intimate, Bowdoin-specific setting makes it all the more personal and difficult to critique.

A few weeks after our conversation in Port A, the Texas sun fading from our cheeks, we wandered into the exhibition gallery in Smith. Our eyes skimmed over hips and thighs and breasts, nervous smiles, knowing smirks and heads thrown back in laughter. There was a sense of familiarity, comfort and reflection, seeing all these bodies so similar to our own. But there was also a nagging sense that we were still viewing women’s bodies as just that: bodies. We were still running circles in Butler’s trap.

We found ourselves desiring an exhibit that moves beyond the female body as spectacle, one that celebrates the beauty of women whose spirits find homes in wide-ranging bodies, sure, but more so the beauty of women who are activists, who are athletes, who are immigrants, who are artists, who are trans. We want to celebrate a womanhood that moves beyond our ability to put on or take off our clothes—a feminism that doesn’t leave us glued to the mirror, contemplating what’s so empowering about gazing at our naked bodies in the first place.

A half hour into our jumbled rant, a mammoth black pickup truck angled its way across the beach. “Nice ass!” A gaggle of college-aged passengers shouted from the cargo bed. Thanks, we thought, settling back into the surf. It felt neither reverential nor reductive. It just was.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy:

- No hate speech, profanity, disrespectful or threatening comments.

- No personal attacks on reporters.

- Comments must be under 200 words.

- You are strongly encouraged to use a real name or identifier ("Class of '92").

- Any comments made with an email address that does not belong to you will get removed.

Amazing piece! Totally agree.