The Hall effect: how a Bowdoin-taught genius made history

February 8, 2019

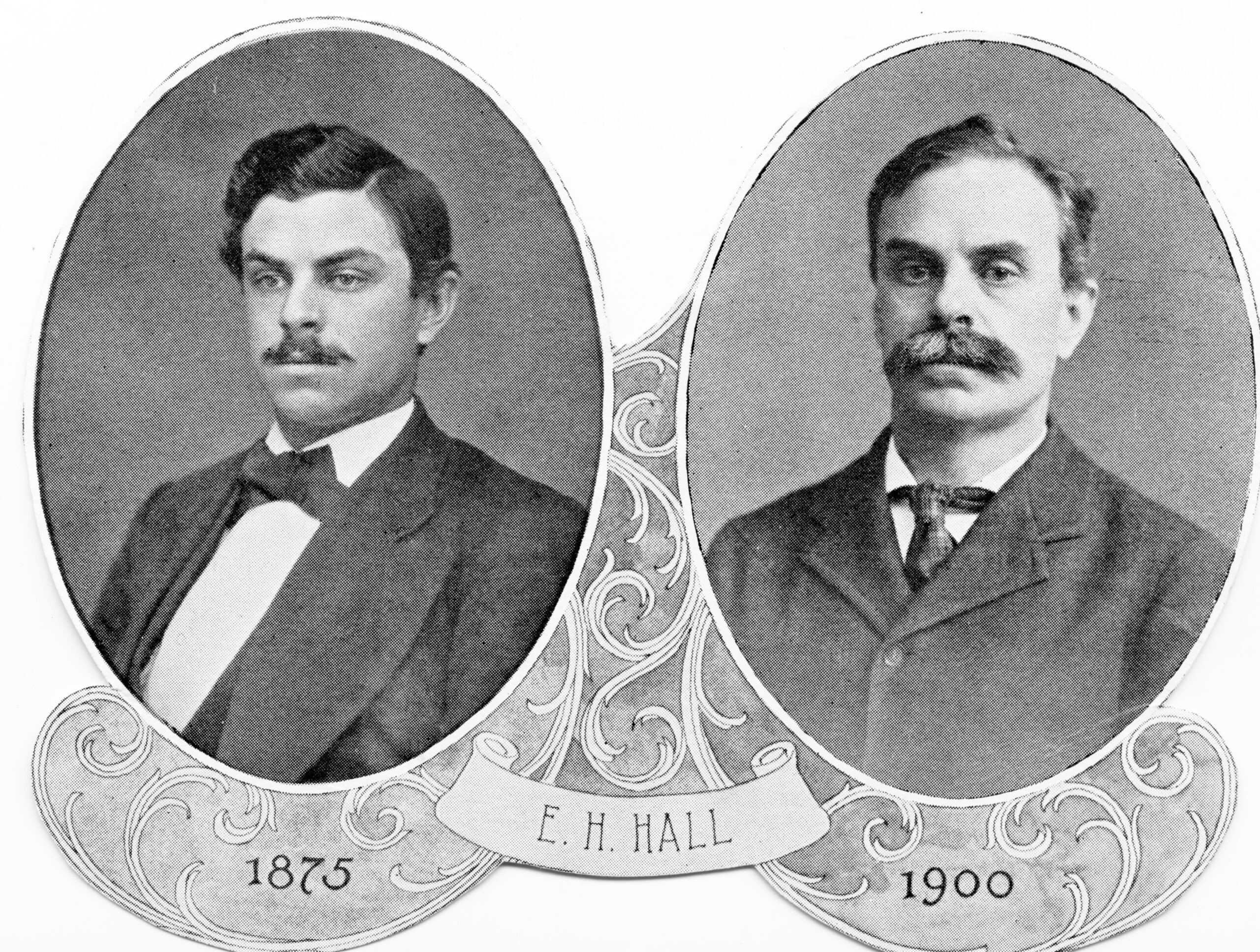

Courtesy George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & Archives

Courtesy George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections & ArchivesBowdoin has no shortage of notable alumni to boast about. Yet unless you’re a physicist or engineer, you might not have heard of Edwin Hall, Bowdoin Class of 1875.

Hall was born in Gorham, Maine on November 7, 1855, and grew up in the area, ultimately attending the College and continuing on to make enormous strides in his respective field of physics that altered the course of fields such as engineering and technology entirely. He is most notable for the discovery of the phenomenon that would come to bear the name “the Hall effect.”

While Hall may not share the same level of name recognition as Nathaniel Hawthorne or Henry Wadsworth-Longfellow, his contributions to science remain essential to modern physics.

“There isn’t an engineer in the world who doesn’t use or know about the Hall effect,” said Professor of Physics and Department Chair Dale Syphers. “There are hundreds of thousands of engineers around the world … millions probably, and they all know who Hall is.”

Hall served as the principal of Gould Academy from 1875 to 1876 and then as the principal of Brunswick High School from 1876 to 1877. He then attended graduate school at Johns Hopkins University, from which he graduated in 1880.

While conducting research at Johns Hopkins in 1979, Hall made a career-defining breakthrough, discovering the “Hall effect.”

In layman’s terms, the Hall effect is the phenomenon observed when a magnetic field runs perpendicular to a charged piece of conductive material, causing the negative particles in the material to gather to one side of the object and the positive to the other. The separation of particles creates a charge that can be measured as voltage. The discovery is used in a variety of types of technology to this day.

“There are all kinds of magnetic sensors and they use the Hall effect,” said Syphers. “They’re used in your automobile and in your phone. They’re used all over the place.”

Aside from its practical applications, Hall’s discovery enabled other physicists to make further discoveries in the area of electromagnetism. Klaus von Klitzing’s discovery of the Quantum Hall effect won him the 1985 Nobel Prize for Physics. Thirteen years later, the trio of Robert Laughlin, Horst Störmer, and Daniel Tsui were awarded the 1998 Nobel Prize for Physics for their discovery of the Fractional Quantum Hall effect.

“There was this second life with the Quantum Hall effect and the Fractional Quantum Hall effect,” Syphers said. “There [were] lots of researchers researching those at [their] peak in the ’80s and ’90s. There were thousands of researchers around the world doing research on this again, [and] it’s all derivative from Hall’s work.”

Hall was also an inspiring educator. In 1895, Hall was appointed as Professor of Physics for Harvard University, where he taught for 26 years before retiring in 1921.

“Hall was one of the key motivators behind putting laboratory experiments in science classes. There were none before then, it was all theoretical,” Syphers said.

After a lifetime of incredible work in the lab and classroom, Hall passed away in Cambridge, Massachusetts on November 20, 1938, at the age of 83.

Hall was awarded for notable contributions to the teaching of physics by the American Physical Society, which is now called the Physics Professional Society. Although Hall never won the Nobel Prize himself, as they were not awarded prior to 1901, he made pathways for future generations to garner the prize.

Despite all of his recognition in the science realm and the benefits society reaps from his discoveries, Edwin Hall is not listed in the section of Bowdoin’s website that lists notable alumni. He is recognized within the physics department, though; an annual award is given out in his honor and there is also a plaque bearing his name on the third floor of Searles, the home of the department.

“That’s what you would call an inside-the-beltway thing,” said Syphers.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: