You can’t buy happiness but you can play King’s Cup

September 21, 2018

This is the story of four American girls—wait—one half-Jamaican, half-Lithuanian girl, Tyrah; one Israeli-born, but Belgian passport-carrying girl, Romi; one Serbian-American girl, me; and the token American amongst us, Cecile. This is the story of how four girls found themselves playing King’s Cup until one in the morning in Kloster bar, near the Södermalm neighborhood in Stockholm.

We had retrieved drinks at this point, some more timidly than others who were still adjusting to this newfound freedom. Cecile and I protected the single chair we managed to scavenge, while the others traveled further in our hunt amid a claustrophobic landscape. In our view, we noticed two men playing a card game. The manner in which the cards were being exchanged, matched by actions, was oddly familiar.

“I’m sorry, are you playing King’s Cup?”

They were, and upon Romi and Tyrah’s return, we joined in their game. Their names were Peter and Alex. Peter Viking—yes, those Vikings—physically resembled his ancestors. As tall as he was wide, he only diverged from his pillaging roots in his beard and mustache, which were brown rather than the Scandinavian blonde. Between “four-floors,” “seven-heavens” and “eight-mates,” the conversation flowed from demonstrations of the various Swedish accents to Peter’s indie-rock band Abisko which was having a performance later that week. He had been involved in ministry service for most of his life, leading youth mission trips on behalf of his church. Since coming out as gay, he confided to us that he has found it difficult to participate in volunteer work in the same way as he had before and now looks for alternative ways to contribute to the public good. He also joined the other 54 percent of Swedes who identify as irreligious.

Alex was a stereotypical political science student. He was a vegan, a lifestyle that led him to work on an organic farm in Costa Rica for one summer in exchange for room and board. At one point during the night, he opened his mouth and reached behind his upper lip to pull out a small, wet parcel. Snus, the newest invention from Big Tobacco, “can give you a high of ten beers,” according to our latest acquaintance. Wiry and cynical, Alex had boyish features and strawberry blonde hair which countered the bitterness with which he spoke with about his lack of faith in governance—a jadedness that usually comes with age. Interestingly, this conviction didn’t push him towards the ideological right as it might in the States; instead, he said that he struggled to find a political party in Sweden that captured his far-left beliefs. “I lean farther left than a political party can afford to represent without alienating too much of the population,” he explained.

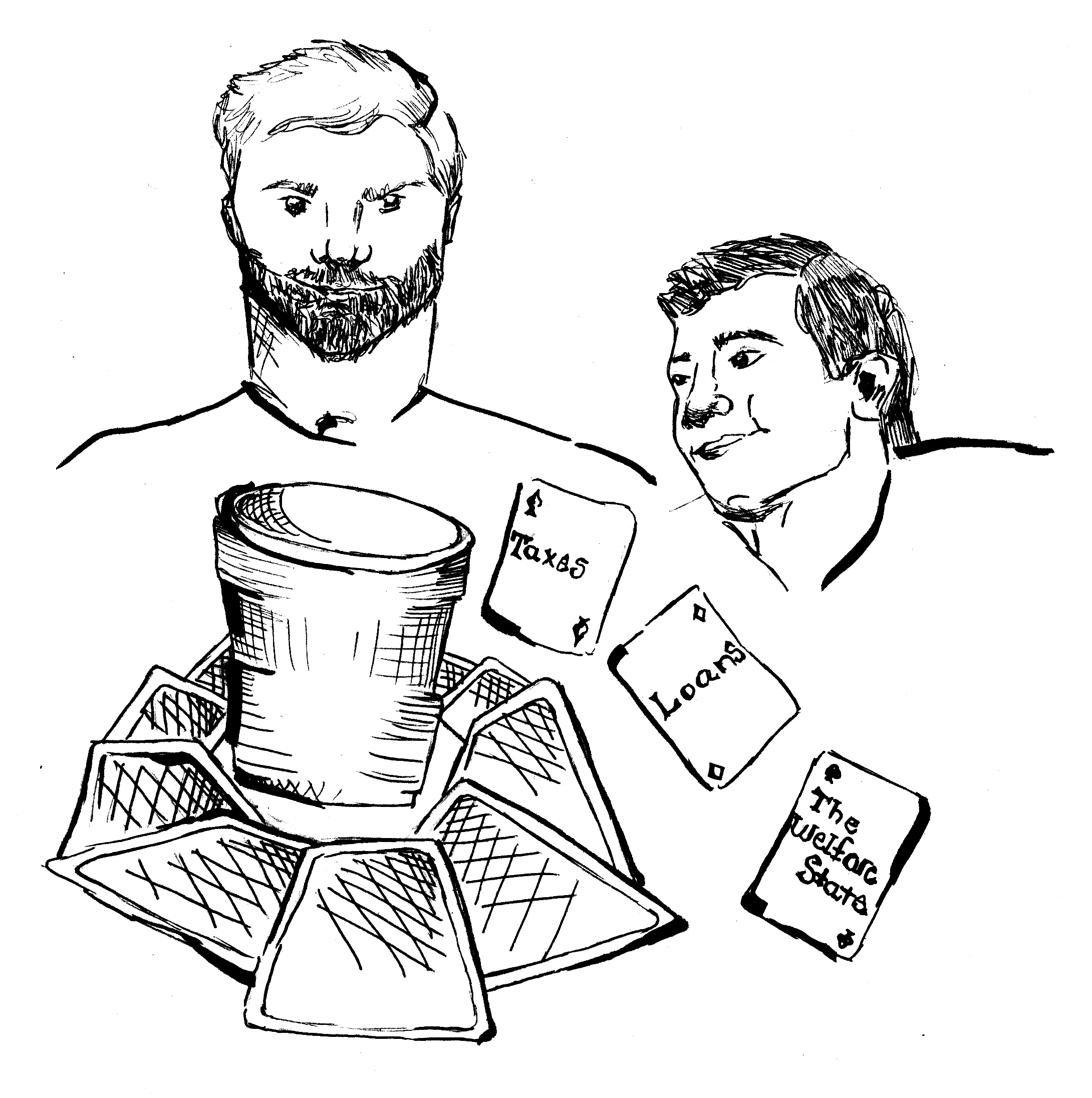

“So,” Cecile’s eyes brightened as she leaned forward, “what do you think about taxation?”

He chuckled. “There isn’t enough of it! You think that 33 percent, or 45 percent or even 55 percent of an income tax is high, right? But imagine how much of your income you’re spending on healthcare. Or indirectly paying for parental leave. Or student loans. Or the shitty public transportation you have—I could apologize, but I’ve ridden your NYC metro. I say, give us more taxes! 50 percent! 60 percent! 70 percent!”

He hit the table with the palm of his hand. The beer pitcher shook, and the beer sloshed and wet the cards on the table. Tyrah left for napkins to clean up the mess.

It was my turn. “So, what do you think about happiness?” Sweden ranks ninth on the World Happiness Index, though it occasionally ties for the top spot.

His eyebrows scrunched, and he leaned back in his chair, musing about where to begin. “How many of you can say that you have a good relationship with your family?”

Three-and-a-half hands raised.

“If I asked a group of Swedes that same question, the response would be significantly different,” he sighed. “The welfare state, while arguably successful in terms of measurable benefits, is not perfect. Take paid parental leave, for example. A great idea in theory, right? Women are given the opportunity to both raise a family as well as pursue a career, and children are able to develop a close relationship with their mother and, after six months, their father. But the time to develop a bond between parent and child ends there. After the age of one, the child starts daycare, a subsidized service provided by the state. As these benefits continue to intervene in the raising of the child, the child becomes emancipated from their parents.”

He paused.

“And this persists over a lifetime. There was a documentary that came out a few years ago about elderly care in Sweden. One story stuck with me: an elderly man passed away in his apartment and wasn’t found for another three weeks afterwards. No one called, no one knocked, no one cared. You would think this is pretty gut-wrenching, right?”

We nodded back.

“But what the documentary showed is that this is normal by Swedish standards—they showed another five or six accounts of an elderly person dying alone. Meanwhile, the rest of the country—their friends, their family, their loved ones—carried on.”

“And we have one of the best standards of retirement homes in the world,” added Peter. “It’s a part of our universal healthcare system.”

The six of us sat, dejected.

There was the screech of chair against floor, a skirmish at the table next to us; we took that as our cue to leave.

Two weeks later, the four American girls found ourselves testing our gastrointestinal limits, nibbling at whale meat and reindeer cheese in Oslo, Norway. Satisfied with our meal, we signaled for the check and began chatting with their server. His name was Ivan, and he was from Croatia. He was one of thousands streaming out of the Balkans as Europe continued to globalize.

He and his wife worked for four years in Croatia before the move to Norway was financially feasible. Those four years supported one month of job-hunting. A living success story, he now works in retail during the day and as a server in the evenings.

“Was it worth it?” I asked. “To uproot yourself? To undertake financial risk? To leave behind another way of life?”

“Absolutely.”

The welfare state may have its flaws—that is true—but it’s the best we have for now.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: