We tolerate hate here

September 14, 2018

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

Phoebe Nichols

Phoebe NicholsWhat was your transition to Bowdoin like? Be careful before you answer, because this is a political question. Your race, your class and your background likely played important roles in your adjustment. This column is a transcription of my own transition as a low-income Black man, as well as a more general reflection of racialized space on campus.

When I was a first year, I slept on a bare mattress for several weeks and did not put on my comforter set until halfway through September, because I could not accept Bowdoin to be my home. Where was my mother? Where was my brother? Where was the food I actually wanted to eat? In Rhode Island.

I remember, during Orientation, I looked through the last edition of the Orient from the previous year. A graduating senior had written a column piece titled, “On Decolonizing Bowdoin: Welcoming People of Color and Women.” The writer, a bisexual, low-income woman of color, reflected on her own relationship with the College. People had asked her if she regretted coming to Bowdoin, if it ever really became her home. Her answer was no to both.

I encourage you to read the full article by Caroline Martínez ’16, but this is a brief summary of her story. Her very existence at Bowdoin felt “odd.” She didn’t want “massages during finals, chocolate-covered strawberries for special events” or “men to grab [her] at College House parties.” She wanted to feel like “a respected individual in [her] own Latina woman skin.” She wanted the College to be a place where you could “hear and feel the struggles of people of color and women across the world.”

Reading this when I did made me incredibly hopeful. My high school was very similar to Bowdoin in demographics, and it addressed diversity and inclusion very poorly. Martínez’s article, however, suggested something different might have been in the works at Bowdoin, that the students may have been truly committed to holding the administration accountable.

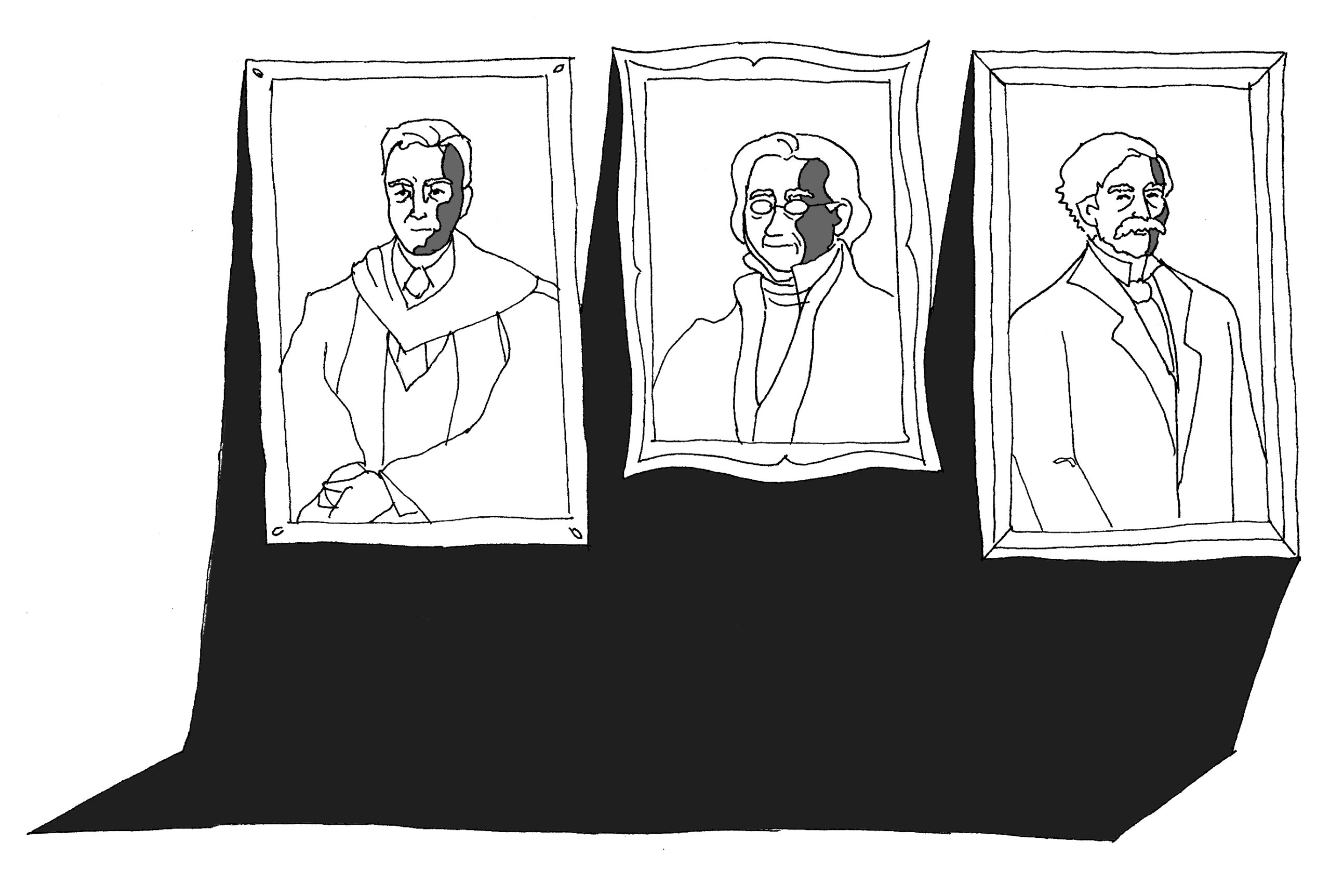

Unfortunately, this hope was quickly dashed by the comment section, where the common sentiment was, “I’m not surprised you don’t feel welcome here, just leave.” These people did not care about her struggle, and they could not understand why buildings named after white men and halls literally lined with portraits of them might be imposing to a woman of color at a college run almost exclusively by white men.

Now, if you similarly misunderstand, think of Hubbard Hall as just one example of many. It is elegant, yes, but also imposing—nobody from my home has wealth like that. In this way, the space’s elegance reinforces whiteness. This is most apparent to me when I am a student in classrooms like these and both my peers and my professors are white. I am given the burden of representing the Black experience to white people so comfortable in this space that they would never deem my people as equal.

If this is to change—and I hope we can recognize that it should—we must radically reconfigure the space and the structure therein of our College. Most importantly, we must move past our tendency to appear one way but act another entirely. Last year, for example, Bowdoin Student Government responded to a bias incident by putting up posters with the words, “We Do Not Tolerate Hate Here,” but what did this accomplish? It was a temporary and fleeting occupation of space, but it did not to address the actual structure of our College which is one that most certainly does tolerate hate.

Martínez said it best, “It doesn’t matter that we say ‘welcome’ with words if in action … this is not the place for people of color and for women.” It’s been three years since she wrote this, but almost nothing has changed on campus. People of color still struggle to graduate in four years. We still experience microaggressions, and we still have to deal with cultural appropriation. When will this stop? How will this stop?

I do not have complete answers to these questions, but I do wonder what this place would look like with buildings named after people of color and with administrators coming from truly diverse backgrounds. If you similarly wonder, or entirely disagree with my critique, catch me in Thorne for brunch on Sunday to continue the conversation.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: