The ‘American Dream’ from the eyes of an immigrant

September 29, 2017

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

This

piece represents the opinion of the author

.

When President Rose addressed the Class of 2020 for the first time last year, he spoke about Bowdoin being our new home—an ode to new beginnings. My attention was drawn to the row of flags behind him—the French flag, American, Afghan, Jamaican. “These are the countries we hail from,” he swept his arms back to showcase our individual backgrounds. “And here, we come together.” My eyes scanned the vibrant displays of patriotism, to find my own. Horizontal stripes of blue, red, white and the national emblem—Serbia.

It’s an odd thing to be a white immigrant in the United States. I lack the classic stereotypes of an immigrant. In fact, upon first glance I am categorized into the second-highest position of privilege: a white, straight female. Since I was three, when my family moved to the United States, my unaccented English has upheld the American mirage. And yet…

The first days of school are always the hardest. Why? Attendance. “Emma Johnson, Kate Keefe, Sa-sa…?” The teacher lifts her head from the sheet, scanning for a responding pair of eyes. “Sa-sha. Jovanovic.” “Oh, they must have made an error in spelling your first name.” “No, actually that’s just how it’s spelled.” She narrows her own eyes, purses her lips and asks, “Russian?” “No, Serbian.” “Even better.” Sarcasm drips in every word.

Explaining why my family is here—and not there—is the next hardest. When I tell someone that I’m from Serbia, a common response is, “How is the situation there?” Having been in and out of war numerous times in the past half-century, Serbia is best known in the Western world as the birthplace of Balkan unrest. And while this may have been a motivator in my family’s decision to move, there hasn’t been violence in Serbia in a decade. The last violent event occurred when I was in the fourth grade.

One day a boy approached me: “I hate your Serbia. Why don’t you go back to where you came from?” In thirteen-year retrospect, I could’ve responded by distinguishing a government’s actions from those of its people. I could’ve explained that most people are not fortunate enough to live in a country in which war has not recently been fought on its soil. I could’ve said that my father sent thousands of job applications all over the world before finally getting a response, an offer to work in Boston. Instead, I cried in the bathroom during recess.

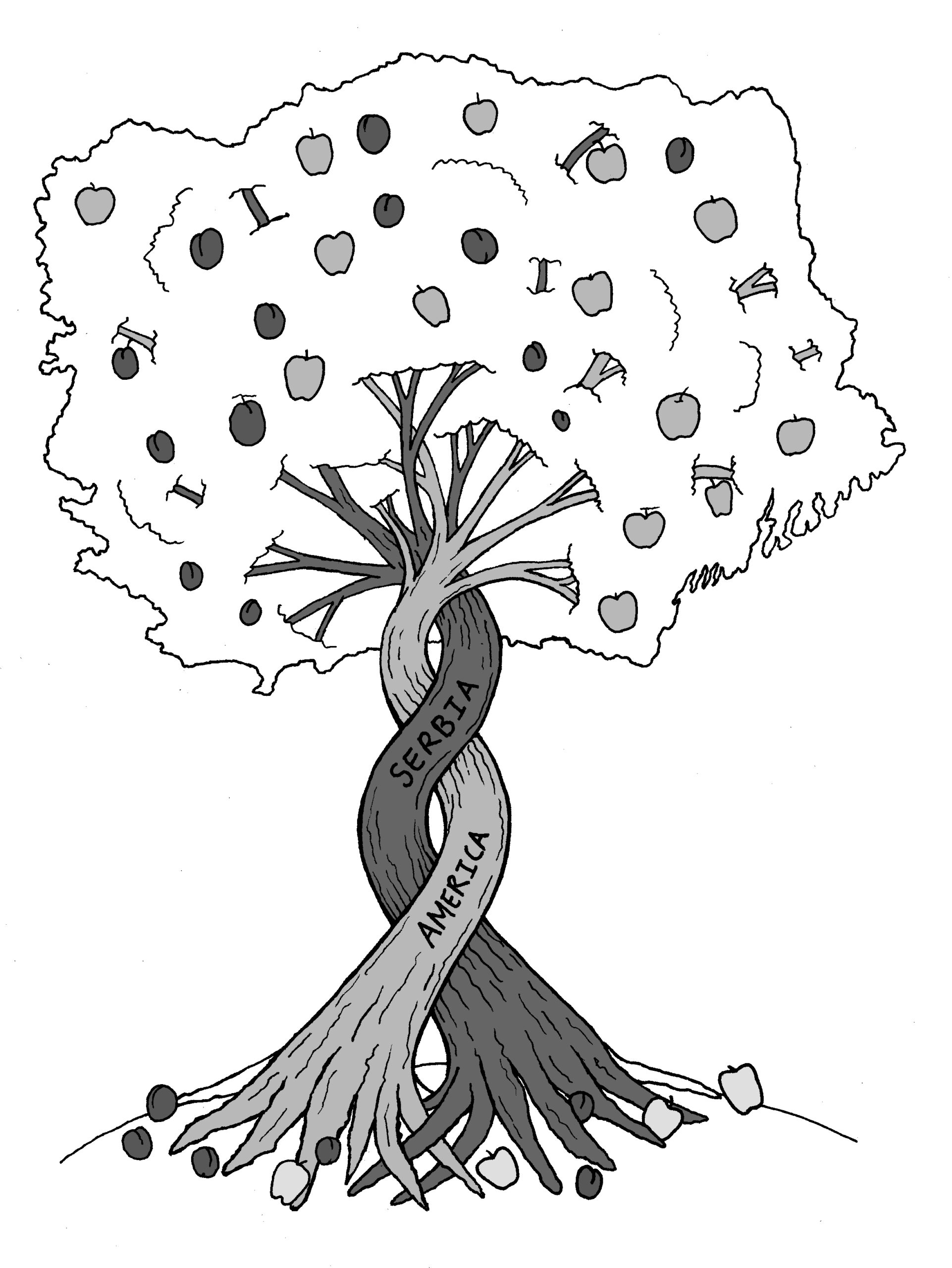

Balancing my Serbian pride and my American home is the next hardest task. When someone asks me, “Where are you from?” I can answer in two ways: “Weymouth, Mass.,” or “Belgrade, Serbia.” It’s an inner conflict of belonging. I love both of my homes—America, for the freedom, liberty and apple trees and Serbia, for the family, history and plum trees. How can I become a member of this American community without betraying my roots? How can I celebrate my heritage without being labeled a foreigner? I need to normalize Serbia’s image in order to normalize my own. So I bring Serbian food to class. I perform Serbian dance at school meetings. I jam out to Taylor Swift. I teach my parents proper grammar. And most importantly, I meet Kaja, Ana, Marko, Matija, Anja, Katya, Luka. Together, as first-generation Serbian-Americans, we find our own balance in the act of assimilation.

Then I came here. Freshman year. Bowdoin. No one knew who I was; I was free to define myself without expectations or limitations. I found myself in a familiar place, wanting to both remain true to myself as well as join the rest. Immigrants are constantly asking themselves, “Am I American enough? Am I ___ enough?” America’s melting pot can be understood as both a coming together of differences, as well as a conforming to a common unity. College is no exception, acting as a pseudo-melting pot. Even on the national scale, we all come from different states, cities, backgrounds to conform to the image of the Bowdoin student, the Polar Bear. There’s freedom now to reinvent yourself, to remind yourself or to remain yourself. Whichever way you choose to identify in this new environment, I am not one to judge. I merely ask that you are consciously forming your identity, and celebrate others as they find their own.

First years, this piece might ring a bell: as I read it to you for the program “More Than Meets the Eye” held during orientation. While there is a note of terror in reading your life story to an audience of 501 strangers, it doesn’t compare to the emotional vulnerability of the readers’ own first rehearsal—16 strangers alone in an empty, silent auditorium with just their words suspended in the air. Some stories brought people to tears, some stories brought unease, some stories brought laughs. From 16 varied directions we found common ground in the practice of storytelling, drawing comfort from the knowledge that someone is listening. And yet, aren’t we storytelling every day? We talk, we text, we exchange—our backgrounds, our hopes, our dreams.

Our dreams. As diverse as the real futures may turn out to be, the values behind the initial dreams are the same—community, integrity, modesty, tenacity, humility. ‘American’ values. While it has been claimed that these values are uniquely American, I’ve found from storytelling—and story listening—that this is not true, that in fact these values transcend borders and transcend patriotism. These values are universally shared. I suggest that the right to dream is a basic human right; the right to aspire to a future without “expectations or limitations,” the right to “reinvent yourself, to remind yourself or remain yourself,” the right to expect equal opportunity in the pursuit of the dream.

The announcement of the DACA repeal directly conflicts with this fundamental right by throwing approximately 800,000 futures into uncertainty. If as a nation we claim to be the common ground for the world’s stories, much like Bowdoin is a common ground for its students, then it’s necessary to conduct policy on that claim. If as a nation we claim the aforementioned values as American ideals, then a failure to uphold them would suggest a failure of national identity. If as individuals we have the privilege to dream, we must seek justice for those whose ambitions deserve validation.

Sasa Jovanovic is a member of the Class of 2020.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: