Soviet propaganda exhibit sheds light on past and present

September 29, 2017

Courtesy of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art

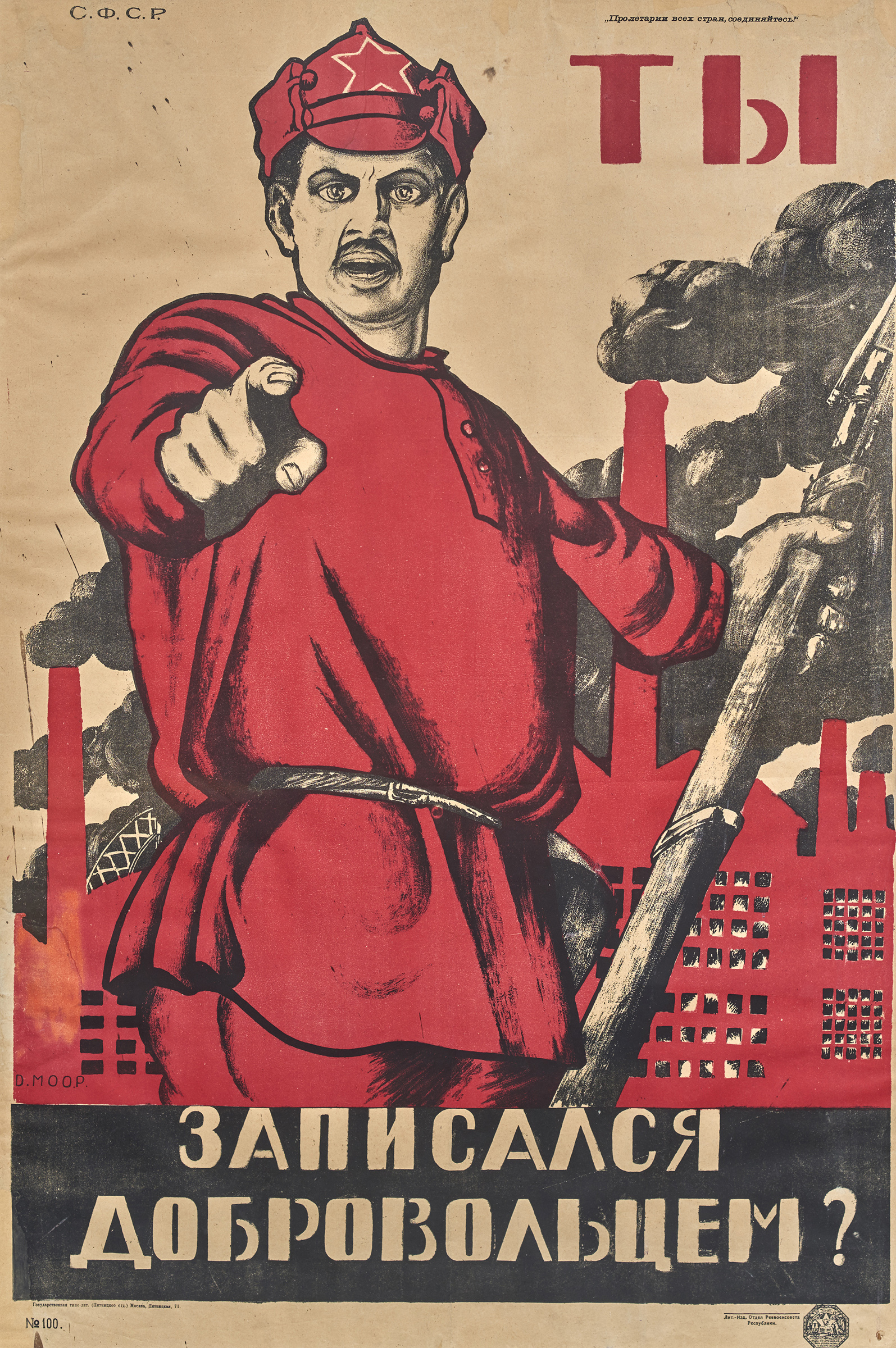

Courtesy of the Bowdoin College Museum of ArtWhen viewed in a modern context, the Soviet propaganda posters in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art’s (BCMA) newest exhibit provide not only insight into the rise and fall of the Soviet Union but also a framework for understanding the present.

The nearly 100 posters on display in “Constructing Revolution: Soviet Propaganda Posters from between the World Wars” largely focus on the 1917 revolution and its aftermath. The posters are on loan to the museum by Svetlana and Eric Silverman ’85 P ’19 and represent a selection of their large personal collection.

According to BCMA Co-Directors Anne and Frank Goodyear, the posters illuminate the intersection of art, culture and politics at a critical historical moment.

“What I think is really thrilling, as an art historian and somebody who focuses on modern and contemporary art, is [that] this exhibition, I think, demonstrates very vividly the role that culture plays—in a very emphatic and sensitive fashion—in shaping people’s ideas about the promise of new political ideals,” said Anne Goodyear.

According to Anne, avant garde artists played a significant role in broadcasting these political ideals. The posters represent not only an ideological revolution but also an aesthetic one, employing new photographic techniques and effects that are still used today.

“The posters themselves begin to reflect this integration of new technologies [and] new expectations of sharing culture with the masses,” she said.

Courtesy of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art

Courtesy of the Bowdoin College Museum of ArtHowever, the Goodyears agree the exhibit is also intended to inspire insights about the present.

“Today, Russia is still very much in the news every day,” said Frank Goodyear. “It’s very interesting to have a leader like Vladimir Putin, who is a very strong, charismatic leader who understands the power of images and power of propaganda to shape public perceptions, even perhaps to influence elections. And so I think this exhibition, though it focuses on an earlier moment and marks the centennial anniversary of the Russian Revolution, does have a lot to say about the world which we live in today.”

Anne Goodyear drew parallels between Russia in 1917 and the U.S. today.

“I think people might, in the future, look at this moment as a revolutionary moment, too,” she said. “We are again at a moment of really, really fast-paced change, a sense of uncertainty, a clash of political ideals, which is playing out around us … Maybe there are a lot of ways in which we can gain a certain degree of perspective on what we’re experiencing now, as well as perhaps [bring] contemporary insights and impressions to [think] about why things evolved the way they did a century ago.”

This semester, Associate Professor of Russian and Department Chair Alyssa Gillespie is teaching a new course inspired by the exhibit and made possible by a grant from the Andrew Mellon Foundation. The course explores the role of Russian women artists from the revolution through the present.

“What really struck me actually, in the exhibition, is how clear it is that the politics and the needs of the society at these two different historical moments really determine what the social roles for women are going to be—what the aesthetics for women are going to be, even for women’s bodies—and how socially engineered [those roles are],” said Gillespie.

Posters from the early 1930s urge women to take part in political life and free themselves from domestic burdens so that they can enter the workforce, while post-war posters encourage women to assume more traditional roles and reflect the society’s need for regeneration of the population.

“Those posters from the 20s and the 30s—they’re remarkably attractive to us as women in our own culture today,” said Gillespie. “It’s a very powerful ideal that’s being put forward, and it’s really striking how current still those same social challenges are for women today in our society.”

Like the Goodyears, Gillespie believes that the works in the exhibit can inform how we approach the present and the sources of information we consume.

“[It] points to the way that really attractive messages, idealistic messages … can be portrayed so effectively, and yet the reality can be so out of sync with it. And it teaches us that we have to be very critical in evaluating the kind of messages that get put out there,” said Gillespie, discussing one of the posters. “I think there are all kinds of ways in which the exhibit could be relevant to the historical moment that we’re living in today, [such as] how does a bald-faced lie get constructed and draw people who are uncritical consumers into it?”

The main exhibit is accompanied by “Dmitri Baltermants: Documenting and Staging a Soviet Reality,” a collection of works by an acclaimed Soviet photojournalist, curated by Johna Cook ’19.

“Constructing Revolution” will be on display at the BCMA until February 11, 2018.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: