Disabled, or how I learned to stop worrying and love my brain

April 7, 2017

Living at school with a disability is tough. As someone who survived a brain infection three years ago and had to relearn to read, speak and walk without falling, I know my fair share of what tough is. During the past two years, I was at home doing nothing but focusing on recovery and rehabilitation. I attended weekly group rehabilitation with other adults with brain injuries (from strokes, trauma, aneurysm, etc.) and settled into a routine with people who work and experience life at the same pace as me. While at home in the “real world,” I regained my confidence and new sense of self despite now living with hearing loss, mild mobility issues and mild cognitive impairment. By summer 2016, I was finally approved (not to mention beating the doctors’ expectations by a couple years) to return to Bowdoin as a full-time student.

Coming back to Bowdoin was big news for me because in my eyes, I could finally become a “normal” young adult again. While it was great to come back, being at Bowdoin proved to be much more difficult than I initially imagined. At home, my peers were mostly adults who have settled well into life, but up here, my peers are all young, active and ambitious (whose intense lifestyle no doubt befuddles anyone over the age of 40). Coming back to school meant revisiting an environment where the pre-brain injury “me” would feel at home. To the “new me,” however, living here is a slap-in-the-face reminder that I am “disabled.”

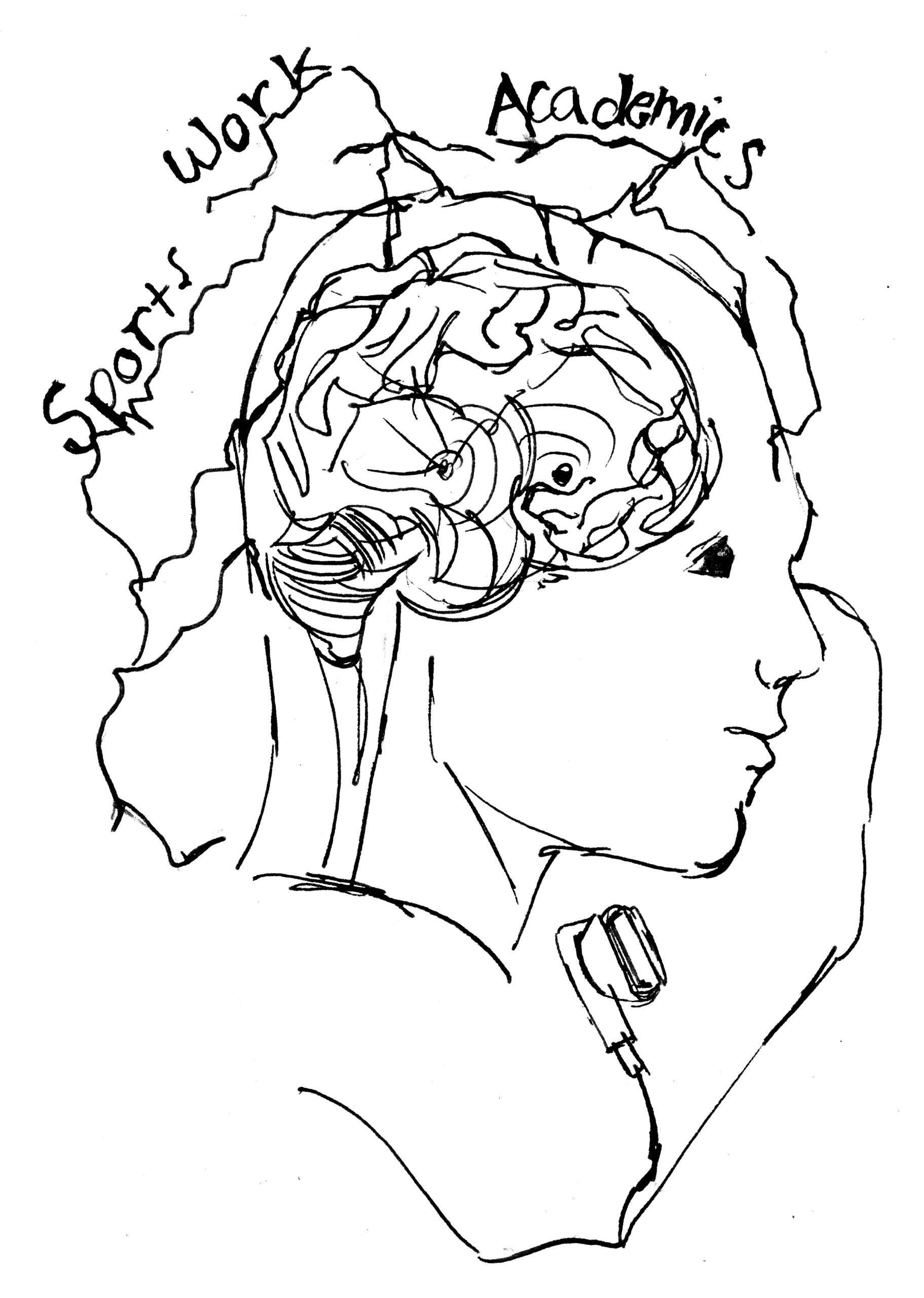

Outside the brain injury community, it is little known that the greatest challenge during recovery is not the long, arduous process of rehabilitation, but the struggle to come to terms with your current state of existence (as the “new you”). This journey, very critical in the recovery process, is fraught with depression, anger, denial, despair and often thoughts of suicide. This part of the recovery process still strikes a raw nerve within me every time I come across old photographs of my days as an athlete or reminisce with my friends about our cherished moments in high school. I came to Bowdoin as a swim recruit and a “straight A” student, goddammit, not as a guy who can’t walk more than 10 minutes outside without the support of a leg brace and who needs the use of assistive technology to compensate for my memory and cognitive impairments.

Being at Bowdoin, I see the person I would have been—partying, playing varsity sports, participating in God knows how many extracurricular activities while (oddly) having enough energy to complain about how much work I have with everyone else. This is a living, breathing reminder of how I imagine the “old me” would’ve been. No matter how hard I try (and yes, I try), I can no longer be like the typical active young person. To survive, I have to make my own adjustments and create my own college experience.

Having a damaged brain that can no longer take in so much stimuli without hours of nausea, headache and feeling downright horrible, I live by my noise cancelling earphones and find strategic seating during meals to minimize the noisy, crowded environments. I avoid large group hangouts because, with my hearing difficulties, I can only keep track of so many lips. I fatigue easily from cognitive tasks (including speaking—the act of taking thoughts and using various cognitive tools we take for granted to produce a comprehensible sentence to whomever the receiving party is), so I limit the activities I do every day based on how I feel. Sometimes this means none. For these reasons, every party or school event requires a serious cost-benefit analysis. I don’t have any concept of how much work is involved in taking four courses—three is a mighty-enough struggle for me, all things considered, thank you very much. On certain days when I’m blown out, I just lay down and stare at blank walls for the entire day. It’s quite an isolated life and totally sucks at times, but I’m having a ball with the few great friends I have here. (Please see The Statler Brothers song “Flowers on the Wall”). I imagine some people may perceive my compensatory strategies as anti-social, some odd quirk or think I “look and act fine” (not knowing I put in two hard years to look so good). But I guess it’s slowly starting to stop bothering me. What empowers me is meeting and knowing other fellow students out there who also struggle with disabilities and have their own hidden stories and “odd behavioral quirks” to share. Some of them may even be a good friend of yours.

Ben Wu is a member of the Class of 2018.

Comments

Before submitting a comment, please review our comment policy. Some key points from the policy: